Margie Bucheit

Q&A

Bucheit, in an interview, is available to share insights on the following:

- Thoughts on what it was like to live under Nazi occupation in France

- How a resistance formed and held together, despite a fractured French citizenry

- Why history might be so much different if not for the French Resistance

- How questions of betrayal and loyalty were key to Resistance membership

- Thoughts about why some French collaborated with the Nazis, while others did not

- Confronting the risk of one’s freedom and life – and courageously stepping up

1.What is your new book about?

WE CHOSE RESISTANCE is a WW2 story about a stubborn, poorly armed, volunteer ‘army’ in rural France that helped turn the tide of war in 1944. My characters, like the true French Resistance, proceed with the best of intentions—to rid France of an oppressive occupying enemy. Their actions, however, sometimes have tragic consequences. Battles will be won, yes, but at a cost. Friendships will realign, families will separate, and sacred beliefs will be questioned

2. What was the resistance like — who was a part of it and what did it do?

Those who supported or fought for the French Resistance included farmers, shop owners, clergy, working people, landed aristocracy and even members of the Vichy Government, a puppet bureaucracy set up when France was divided in half in 1940. Resistance members had major political differences, but chose to put those aside to fight Hitler, their common enemy. In 1943 the enemy began recruiting young people to work in their factories. Distraught family members encouraged their children to hide or leave home. A groundswell of men and women aged 15-25 joined the Resistance movement during this time.

3. Anyone in the resistance risked their life. Why did they do it?

Henri Pean, a Catholic curate in central France, helped the oppressed and downed Allied aviators escape through the ‘Marie-Claire’ Resistance network. Pean also gathered intelligence for the Allies. In 1944 his actions were discovered. He was arrested and tortured. He died on a train headed for German concentration camps.

Viscomtesse Marie Therese de Poix, also from central France, worked with Henri Pean. She helped people targeted by the Nazi regime escape France until her activities were also discovered. Arrested by the gestapo and sent to Ravensbruck in 1943, she survived.

Chantal de Pouilly and her family risked everything to hide downed, injured, Allied pilots in their home. Her siblings were part of a Resistance network that helped oppressed people leave occupied France. Chantal’s story inspired my curiosity about local Resistance activities that helped win the war.

Jean Moulin, whom Charles DeGaulle named defacto head of the French Resistance. Moulin is credited with unifying the Resistance movement, integrating their political differences, instilling discipline and giving structure to the fractured organization. He was captured by the Nazi Gestapo’s notorious Klaus Barbie and tortured. He died from his injuries in Metz, France.

4. How does your story expose the hardships the French Resistance endured to help defeat such a powerful enemy?

My story focuses on the importance of trust in relationships. During WW2, it was important to know a person’s background. Members of the Resistance had only each other to rely upon. Sometimes local communities viewed them as ‘terrorists’ because of their actions. Often, the occupying regime would kill or torture innocent French following Resistance actions against the Reich, so secretiveness was imperative. To keep hidden, many Resisters lived rough in forests throughout France, often scrounging for food and weapons. Some had only a family’s hunting rifle for protection, or if they were lucky, weapons stolen from the Germans. It wasn’t until late in 1943 that better guns were obtained through the Allies.

5. Is it true that some people in France supported the Hitler regime?

Yes. Prior to the war, France was in political turmoil and some French thought the German occupation brought order to the country. The far left (socialists and communists) had formed what’s called the popular front. Their liberal views are often touted as being the reason for France’s downfall, but in fact, militarily, the Germans had superior tanks and outwitted the French strategically.

The country was divided in half after the takeover, and a former WW1 war hero, Marechal Petain, was appointed Vice Premier of Vichy by Hitler. Petain antagonized many French with his traditional demands: that women stay home and not work, for instance. His changing of the national motto from Liberty, Equality and Fraternity to Work, Family, Labor was very unpopular. Petain also turned on the Jewish population and blamed them, along with the liberals, for the downfall of France. His actions, while not fascist, were seen as being very authoritarian. It is Petain who developed the Milice, a French police force dedicated to finding and arresting members of the Resistance. There is an excellent article about this time in Smithsonian magazine. See: Was Vichy France a Puppet Government or a Willing Nazi Collaborator? written by Lorraine Boissoneault on November 9, 2017.

6. What type of research about the rural resistance in France did you undertake?

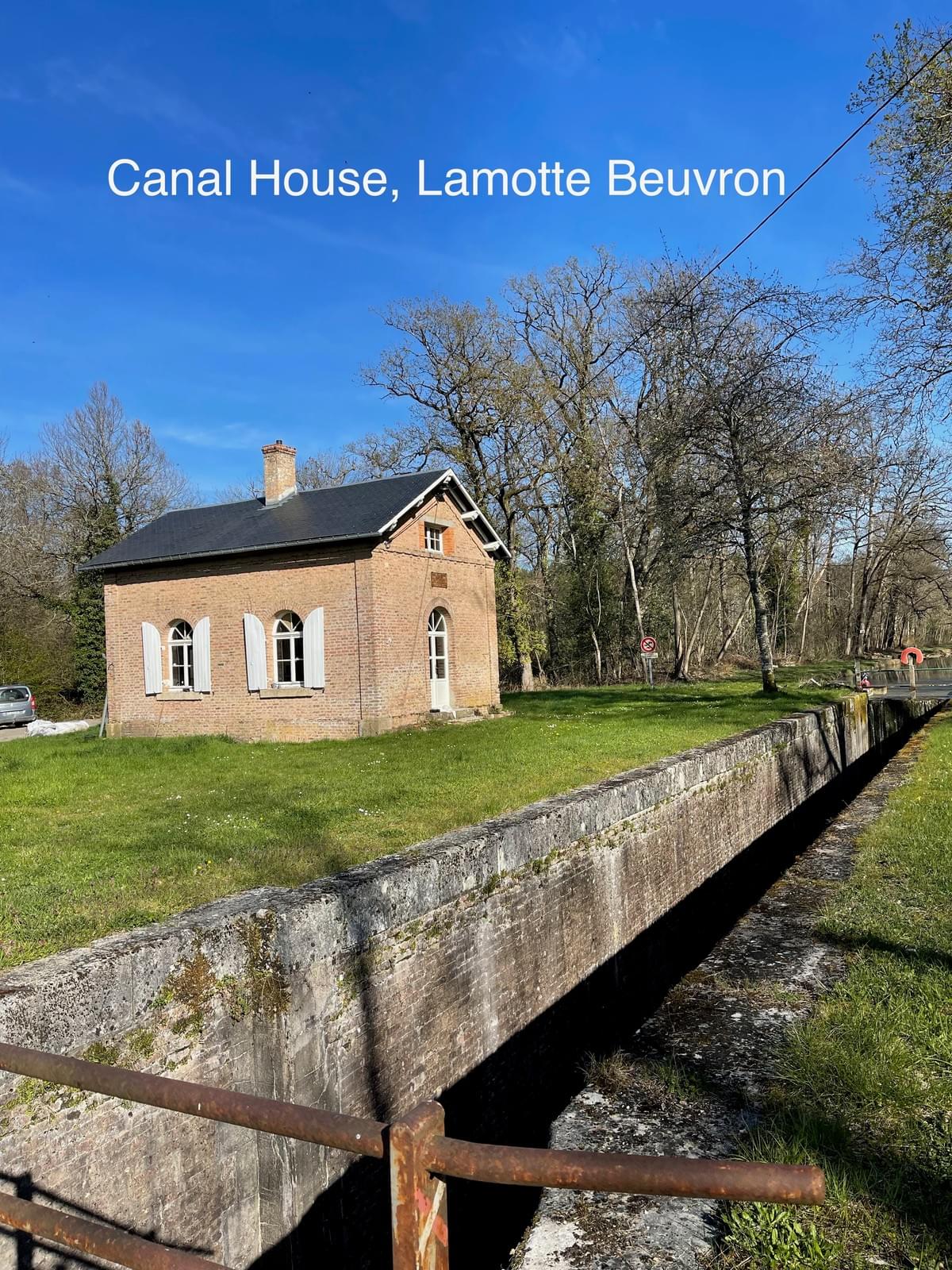

My research began with interviews. While having dinner with French friends, familial stories of the Resistance emerged. Elderly family members who were children during WW2 recounted family involvement with the Resistance. Interviews with Chantal de Pouilly before she died, and two other elderly French citizens helped to clarify what the occupation was like, who participated in Resistance movements, and how even children had a part to play. Further research involved reading about the French Resistance, particularly books about local ‘circuits,’ such as the ones in towns near where I live— La Ferte St. Aubin and Souesmes. The circuits there were betrayed by enemy informants within their communities. Some publications of GRAHS (Groupe de Recherches Archaeoloques et Historiques were also instrumental. And to better understand the Resistance itself, I visited museums throughout France dedicated to the movement.

7. When you came upon firsthand accounts of what these Resistance fighters risked and did, what most sticks out?

The hard choices they had to make. If they choose to follow their inner conscience, they endangered not only themselves but their families. It took courage to decide to go against such a powerful political structure as Hitler’s Reich. Sometimes Resistance members completely cut ties with their families and friends to protect them.

8. What allowed for these untrained ordinary citizens to overcome numerous limitations and fears to make valuable contributions to the defeat of the enemy?

The courage and dedication of those who joined the Resistance movement carried them through. But also, Churchill’s Special Operations Executive (SOE) agents began developing networks in France with the Resistance. By 1944, the two very different entities had formed an alliance that helped win the war. The Resistance often hid SOE couriers, and couriers helped organize Resistance efforts in tandem with Allied actions.

9. What inspired you to write this book?

Interviews with Chantal de Pouilly and two others who lived during that time. Also, when I began writing this, there seemed to be limited knowledge of how the Resistance helped prepare the ground prior to the Allied invasion on June 6, 1944—especially regarding small, local, actions. Americans with whom I spoke knew little about the French Resistance movement or about the politics that led to its creation.

10. It’s the 80th anniversary of the end of World War II. Upon reflection, what role did resistance play in the war?

For me, the Resistance movement was instrumental to the Allied success. Their efforts and sacrifices remind me of early American colonists who fought a well-armed British monarchy. Both groups risked everything to defend their rights: freedom from tyranny and independence from authoritarianism.

11. You are a journalist, so why did you choose to write about the resistance as historical fiction and not as a history book?

While there are known facts about what happened during that time, writing this as a novel allowed the freedom to explore the day to day lives of those who were a part of the Resistance. I also wanted to illustrate how people from all walks of life joined the movement. One interesting fact that did come up was the Parisian Jesuit decision to split with Rome during the war. Rome backed the Vichy and Nazi regimes. The Jesuits in Paris sided with the Resistance. Most helped people escape France or had printing machines to make counterfeit identity cards. There were also Catholic clerics in France who fought alongside Resistance members.

12. How would you describe your writing style?

I like to immerse myself in the setting before beginning a story. It helps me understand the characters and how they lived, what hardships they faced and what pleasures. I like to be descriptive, to let readers experience the setting where the action happens. ‘Setting’ is an important ‘character’ in a story.

13. How did you put yourself into the mindset and customs of the French from eight decades ago and go about crafting your book’s dialogue?

Much of this is conjecture. But through interviews, I was better able to understand how difficult it was to live during that time. Alliances and secrecy were more than important. A person could be arrested or a network exposed if there was a betrayal. A stranger had to be introduced by someone ‘known’ before being welcomed. My husband and I have encountered this type of guarded behavior even today.

14. Tell us about the main characters. Who will play the lead characters in the movie?

I love all of my characters but three stood out for my beta readers as the most charismatic: Gerard, a young member of a Resistance circuit, Dee, an Allied spy, and Martin, a young boy whose parents embrace the Nazi regime (he does not).

15. You spend a lot of time in France. What connects you to France and draws you to it?

My husband, who is a biomedical researcher, has worked collaboratively with a university in France for many years. We have grown to love the country, its customs, and its people. Of course, France is known for its wonderful food, but the food itself is an example of French culture. It’s not just about the food, it’s a meal lovingly prepared in someone’s home that lasts for an afternoon, where all matter of things are discussed, including politics and religion. It’s a restaurant chef who takes time to make sure the presentation of the food on the plate pleases the diner at the table, even before the meal is eaten.

16. Why was France involved in World War II?

France did not choose to be involved in WW2. Germany invaded the country. France had no choice. To this day, some fault Marechal Phillippe Petain who was the leader of the French forces before being named Vice Premier, for how easily he surrendered his country to the Nazi regime.

17. What was it like to live under Nazi occupation?

Oppressive and frightening by some accounts. Most likely very stressful. I think about current communities of color in the United States who must have similar feelings of oppression. The Brown shirts in pre-war and Nazi Germany, officially known as Storm Troopers, used similar tactics to today’s ICE agents in the United States to arrest and oppress the German population.

18. How did the resistance fighters know who to trust? How did they get reliable information about the war?

This was always tricky. Strangers were never immediately trusted, including SOE agents. Secret codes were developed sometimes linked to well-known folk songs of a region. In the early days of the French Resistance, there was fear that Britain also wanted to take over France, even though that was not the case. Trust had to be proven. There was always the chance that someone was a plant, put there by the Germans to inform —as proven by the raids on a Resistance training site in La Ferte St. Aubin.

19. How was England’s Prime Minister, Winston Churchill, involved in the French Resistance?

Churchill developed the Special Operations Executive, a spy network that sent agents into France to disrupt enemy activities in any way possible. His agents developed ties with the French Resistance and as war progressed, the two groups formed a strong alliance. I found the work of one of his agents particularly compelling. Pearl Witherington Cornioley, code named Pauline, was charged with coordinating SOE and Allied activities in a network of more than 2,000 Resistance fighters in central France in 1944. She was also known as one of SOE’s best snipers. She chose to keep a low profile after the war and move on with her life.

20. Your story surrounds the months before and after D-Day. Why was that such a significant battle in the war?

I encourage any American who has not been to the Normandy beaches and battlefields to visit. What the Allies accomplished is astounding. Thousands were killed on the beaches of Normandy, shot by German forces entrenched in cement fortresses in cliffs above those beaches. Churchill’s strategy was brilliant, of creating a port where none existed, by sinking barges in the shallows on one of those beaches. It took the enemy by surprise and gave the Allies a beach head from which to launch troops. I am not sure Americans know that on Veterans Day and Armistice Day (May 8), throughout Europe, Europeans STILL tend to the grave sites of American soldiers killed during the wars.

21. Is the No Kings protest a form of resistance against the government today? Are there parallels to now and then?

Personally, I view the No Kings protests as a strong form of speaking out, of voicing discontent. By definition, resistance is a form of discontent. By contrast, the French refer to the current United States protests as ‘demonstrations.’ When the French resist and protest, they block roads, organize strikes, and disrupt access to essential buildings and services. In terms of parallels, the actions of the current US government against people of color is alarmingly reminiscent of the Brown shirts, Hitler’s Storm Trooper militia that was given free rein to silence voices of dissent, seemingly outside the rule of law.

Website created by Ben Feinblum Media